How these hackers (almost) stole $2 billion from Banks around the World

In one part of the world, surveillance footage shows ATMs spitting cash into people’s hands without any explanation. Halfway around the world, a broken printer hides $951 million being stolen from the national reserves of Bangladesh. Two separate heists. One playbook, These hackers will amaze you!

These are the riveting stories of how two hacker groups stole millions from banks around the world without even setting foot inside one.

How these hackers stole (almost) $1 billion from banks

2014, Ukraine. Surveillance cameras at local banks capture inexplicable moments: ATMs start to spontaneously dispense cash into the open air. No card, no PIN, no physical interaction at all. Pedestrians pocket the unexpected bounty and make themselves scarce.

Imagine being a bank official watching the surveillance footage, the thumping in your head roars. This isn’t possible! You call your cybersecurity specialists, urging them to solve these random, unpredictable, and utterly inexplicable occurrences.

The cybersecurity specialists pour through the ATM hard drives for clues. Yet, a little peeved at themselves, they tell you they can’t find much – no suspicious files, no malware – maybe just an unusual VPN setup that they cannot really explain. They dismiss the incidents as sophisticated malware attacks, and leave it at that.

A couple of months later, at exactly 3 am, one of the cybersecurity specialists who we are going to nickname “Pete”, gets a panicked phone call. A bank representative insists that Pete urgently contacts another number. Moments later, he’s speaking with the Chief Security Officer of a major local bank.

What he hears rattles his stomach. Company data was being sent from the bank’s domain controller to the People’s Republic of China right at that moment.

The domain controller is the very heart of a server network. In a Windows environment, the domain controller is the main server that controls everything. Someone had gained control of their domain controller, that was huge!

The first signs something was wrong

Late that night, Pete stepped into the quiet office building, greeted by the panicked account manager.

Time was of the essence. As Pete went through the flickering glow of the computer screens, he soon discovered the hidden malware – an insidious piece of software designed to allow a third party to secretly observe every keystroke made on the computer, and remote control it.

It dawned on Pete that at that very moment, someone could be watching them and their every move. So Pete got to work, quickly scripting a powerful batch file designed to purge the intruder from the computer. Pete and his team ran the scripts on all the bank’s computers, repeating the process several times until no trace of the malware remained.

But Pete knew his work was far from finished. He saved isolated samples of the malicious code to dissect and trace its origins.

In the following days, they discovered that the malware was installed through a targeted spear-phishing email campaign directed towards various employees. The emails contained a CPL file – a seemingly harmless Windows Control Panel extension that was actually executable, and capable of running malicious code.

The infection – hackers knew what they were doing

Now meet John. John is working a boring corporate job at a big bank. It is a Monday morning, and John is staring at an Excel sheet, waiting for lunch, when an email arrives in his inbox titled “Contract details”. He gets dozens of such emails a week.

He opens the email and reads:

“Good day! I send you our contact details. The amount of deposit 32 million rubles and 00 kopecks, for a period of 366 days, % year – end contribution term”

Attached to the email is a word document (which, unknown to him, it also acts as a software executable) titled “Accordance to Federal Law”. John opens the document, reads the rather boring details, closes it and then leaves for lunch never to think again of that weird email.

But that’s how the hackers got in. Once the remote code gets executed, the Carbanak malware is installed on John’s corporate laptop.

Now the hackers can observe John’s every email, learn how to mimic and impersonate his corporate persona in every tiny detail. Patience is key here.

Then, after learning as much as possible from John, the hackers start to act, sending emails in John’s name to other coworkers, and thus spreading the malware to multiple PCs and corporate laptops.

As they jump through the network, the hackers look for the highest-access points, the domain controller we were talking about earlier.

Inside the network

By carefully deploying invisible keyloggers and hidden screenshot software into the breached devices, hackers gained a complete understanding of the bank’s financial systems, internal routines, and operational methods.

Once they had gathered enough intelligence, the criminals moved swiftly to withdraw the money. Depending on each bank’s vulnerabilities, they managed to transfer large sums through the international SWIFT network straight into their own offshore accounts. Other times, they created fake bank accounts by changing the banks’ internal databases, and inflating balances. Then they would trigger ATMs to spit out cash directly in the hands of waiting accomplices (called “money mules”).

We’re not just talking about a single bank here. We’re talking about over 100, from Eastern Europe, to the Middle East, Asia and Africa. Over half of these attacks succeeded, with each bank losing between $2.5 million and $10 million in total. In total, the hacker group managed to net approximately 1 billion dollars.

The aftermath

From infection to discovery, each robbery took between 2 and 4 months, carried out with ruthless efficiency.

It all began subtly in December 2013, with the first infections. Months later, between February and April 2014, the hackers succeeded in extracting the first stolen funds, with the attacks peaking in June 2014.

After the world finally found out what was happening, banks began to purge the malware out of their institutions. Nevertheless, the hackers operated from the shadows until 2018.

In March 2018, Spanish police, working closely with Europol and law enforcements from multiple countries, arrested the group’s leader – Denis K – in a carefully planned operation in Alicante, Spain.

There were other arrests around the globe as well. In Kazakhstan, authorities caught 2 more hackers, sentencing them to lengthy prison terms, but some Carbanak hackers still remain unknown.

In the end, after more than 5 years, the sophisticated Carbanak operation was ended by authorities all over the globe. It was one of the most complex and financially damaging bank heists in history.

But wait until you hear this next one!

The Lazarus heist – hackers hacked a printer and all hell broke loose

It’s a quiet Thursday night in Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh. Staff begin to leave for the weekend. Friday is a holy day in Bangladesh, and it is the start of the weekend.

But unknown to them, in a hotel room in another part of the world, a group of people are sitting on their computers, waiting for the clock to strike 20:00 in Bangladesh.

Months of preparation had led to this moment. A carefully-crafted phishing email, a polite job application from a said “Rasel Ahlam” sent a year earlier, had been their way in.

All it took was for a droopy employee to click it, download the file, and the silent infection began.

For nearly a year, they waited, watched, learned and prepared. They now know everything about Bangladesh’s bank systems, workflows, employees’ habits and SWIFT transactions. They are patient, disciplined and precise. Their target is nothing less than the country’s foreign currency reserves held at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

By 20:36 Bangladesh time, their plan is in motion.

35 transfer instructions, amounting to almost 1 billion dollars, are sent from the Bangladesh Bank’s account at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York to accounts in the Philippines and Sri Lanka.

Should we repeat again?! A billion dollars! And the timing was the perfect trap.

The federal reserve receives the orders

It is now Friday in Bangladesh, which is essentially a weekend.The bank is effectively closed, its offices silent.

But in New York, it is Thursday morning, and it is business as usual. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York has received the 35 SWIFT instructions from the Bank of Bangladesh – which looked like they were authorized and validated by the bank itself.

To the Fed, it seems like just another busy day – money moving between different institutions. But a few curious details stand out to them in some of these 35 transactions.

The word “Jupiter” that appears in one of the transaction’s beneficiary addresses is a name tied to an Iranian shipping company under U.S. sanctions. The transaction is flagged for review.

Then another transaction that meant for a Sri Lankan charity has a misspelled word – “Shalika Fundation”. The Fed also flagged this one.

The Fed’s system stopped these transactions until clarifications were offered by the Bangladesh bank, but some of them – totalling $81 million – cleared. Money gone!

A printer that could have stopped it all

In Bangladesh, the few employees who are working over the weekend notice the main printer terminal that was printing SWIFT orders was not working. But it didn’t seem like a critical issue – with Friday and Saturday being the weekend, no one was around to fix it, and they didn’t really care.

But they should have!

You see, that printer is no ordinary printer. It is the only way the Bangladesh Bank employees can see the reports of the SWIFT transactions being made by the bank.

So, they had no idea about those unauthorized SWIFT transactions.

Who approved the $951 million

It is now Sunday morning, February 7th, which is the first working day after the weekend in Bangladesh.

The IT team finally fixed the jammed printer on the 10th floor of Bangladesh Bank.

But as the printer whirs back to life, it begins spewing a backlog of SWIFT transaction records – page after page of silent, monotonous chaos.

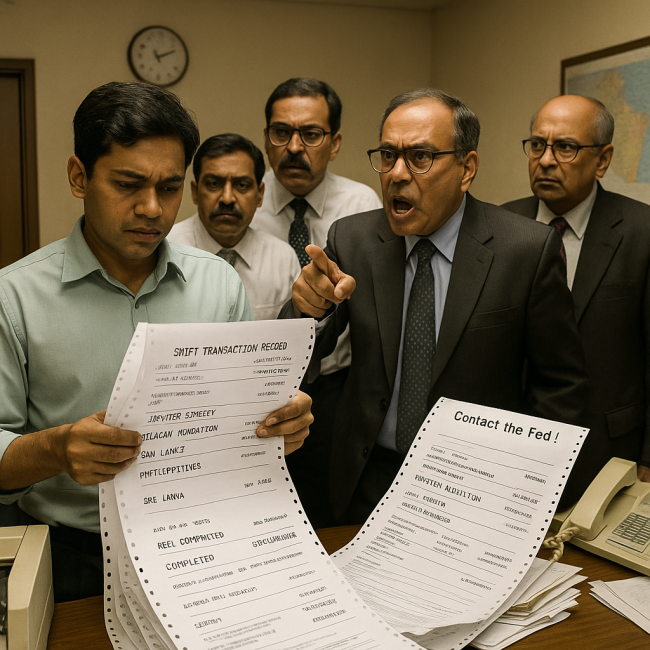

Mahmud, a junior officer at the bank, grabs the printouts, his heart sinking with every line.

$951 million in outgoing transfers. Some marked “completed”, others flagged with urgent inquiries from the Federal Reserve.

Mahmud rushes to his supervisor. Within minutes, the room is packed with senior bank officials, all staring at the thick stack of printouts. Names like Jupiter Street, Shalika Fundation, Sri Lanka and the Phillipines stand out like insults on the paper.

“Contact the Fed!”, shouts one manager.

But it is Sunday in New York, it is the weekend. The Federal Reserve is closed.

Remember when we said the perfect trap was timing?! They are now trapped.

The Aftermath

As the dust settles, the Bangladesh Bank’s leadership contacts a cybersecurity firm to investigate what has happened and how deep the hack went.

The first chilling discovery comes quickly: the hackers did not exploit a flaw in SWIFT itself, as they first believed. Instead, they compromised the bank’s internal network and gained access to the SWIFT software from inside, appearing as genuine employees making legitimate transfers in the name of the bank.

After further digging, they discovered malware disguised as… guess what… a printer driver.

So, the attackers didn’t only manage to take advantage of the bank’s network by spying on transaction logs, intercepting messages and sabotaging the SWIFT system – they also managed to sabotage the SWIFT printer terminal – a simple trick that delayed the detection of the theft, giving them just enough time to move the stolen money.

The investigators found a certain pattern in the malware code that led them to believe the hackers behind the heist were the infamous Lazarus Group, a North Korean hacking group who was previously involved in cyber attacks on South Korean financial institutions and even Sony Pictures.

Follow the money

Thanks to the Federal Bank of New York’s vigilance, only $81 million out of the almost $1billion, made it through.

But where did those $81 million go?

As the investigators comb through the SWIFT logs, and the Federal Reserve’s messages, a pattern emerges: Rizal Commercial Banking Corporation (RCBC), on Jupiter Street, Manila.

The RCBC branch on Jupiter Street was a pretty unremarkable building – tucked between a small hotel and a dental clinic, on Jupiter Street, in the capital of the Philippines. But behind its glass doors, 4 accounts were set up in May 2015 – long before the heist.

The applications seemed cleaned at a first glance, but upon closer inspection, they discovered that the IDs used were poor-quality fakes, each account holder had the same job title and salary, all 4 accounts were opened with small deposits and stood untouched for nearly a year.

Until the night of the heist. Suddenly, on 4th February, millions flowed in.

But they didn’t stay there.

The scandal goes public

The hackers knew that the RCBC bank accounts could be traced, frozen and investigated. So they moved fast.

They transferred some of the funds to Philrem, a local currency exchange company where dollars were exchanged for Philippine pesos.

The rest of the money took the path of the Manilla’s casinos.

$30 million went into Solaire Resort & Casino, another $12 million to Midas Hotel and Casino.

Millions more were poured into middlemen who arranged private gambling experiences for wealthy Chinese clients.

The casinos in the Philippines were the perfect laundering machines in 2016. Once the money became chips, it was out of sight.

Inside the VIP lounges of these casinos, the millions stolen from the Bangladesh Bank were wagered at baccarat – a gambling game with simple rules, and high stakes.

The chips changed hands, and cashed out as clean winnings. And so they went from stolen dollars to clean casino payouts.

In their attempt to find the money, the Bangladesh Bank’s investigators also discovered that some of the RCBC officials had tried to cover up the transactions, by deleting records.

The scandal would eventually become public, prompting the Philippine Senate to launch an investigation with bank managers, and casino operators.

But as they dug deeper, the money itself was disappearing.

In the months that followed, the Bangladesh Bank managed to reclaim $16 million from a casino operator tied to the Midas Casino laundering machine. But beyond that, the trail became thin, the accounts drained and the casino players were gone.

The Bank of Bangladesh filed lawsuits, pursued court orders and launched diplomatic protests, but the rest – around $65 million – vanished, and eventually ended up somewhere in North Korea, as investigators believe.